Essential Blues Recording

Charlie Musselwhite – Musselwhite’s Apex Collection

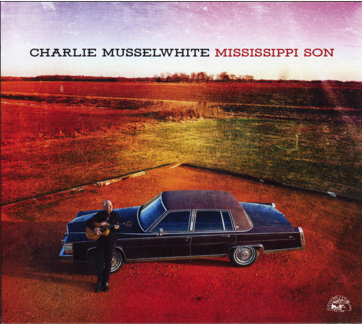

Charlie Musselwhite – Mississippi Son – Alligator Records ALCD 5009

With a roughly 60-year blues career in his rearview mirror, and close to 40 albums to his name, Charlie Musselwhite’s Mississippi Son represents the pinnacle of his recorded output. Among the sheer noise and volume of much of the recorded output by today’s blues practitioners, Musselwhite delivers a stunning summation of his long, heralded career and life, giving listeners the benefits of his earned world wisdom and observations, within a stark and stripped-down framework. Here we have deep reflection of Musselwhite’s roots and influences. This collection is not an homage; rather, it is his necessary late-life journey. It’s not often enough that blues collections such as this are made.

Mississippi Son was recorded in Clarksdale, MS, with Musselwhite supplying both acoustic and electric guitar work on each cut, along with the harmonica duties and vocals, with only the support of Ricky Martin on drums, and Barry Bays on acoustic bass. Musselwhite recently moved from northern California to Clarksdale, and his musical blues imagery, born from deeply living the blues, moved with him.

What Musselwhite has done here is provide deeply soulful material from a patriarchal blues sage, urging his audience to get on-board his blues train. What from others may sound like cliches are very real to Musselwhite, who here is a grand story teller, a prophet of life, if you will. Here we have a seasoned blues master on a personal journey within a catalog of songs he truly feels and appreciates. It is not often that a collection is released without some filler, but that is not the case here. The eight Musselwhite originals, and six covers, represent that ideal meeting place when a man is in his own head playing just for himself.

While most blues fans most likely identify Musselwhite as a blues harmonica giant, he is equally proficient on guitar. On this collection, Musselwhite presents the listener with his brand of ample, effective acoustic and electric blues guitar abilities, the likes of which the blues realm has all but forgotten, instead in favor of brash delivery and volume (“My Road Lies In Darkness”). His guitar ideally frames each blues song’s mood and message. It is not slick, it is not aggressive, nor is it unoriginal.

Musselwhite’s vocals are subdued in their delivery. His voice is weary, yet warm, itself a vehicle to express life’s summations. With Musselwhite, there is no reason to shout, as when an artist such as Musselwhite’s words are authentic and validated by the benefit of a blues life having been fully lived. His messages come through completely and without any notions of being vague. Musselwhite sings in a half-spoken manner here, clear and concise, doing so as to assure that the blues story and the words backing it up are most important aspects (“The Dark”). On this collection, Musselwhite’s verbal strolls dole-out learnt advice. A listener gets the distinct impression that he truly believes, and bears the weight of, the observations and lessons learned in his vast experiences.

Musselwhite’s harmonica work, when deployed, weaves in and out to great effect. His harmonica efforts are of course legendary, and here they intertwine seamlessly with his guitar phrases, and are supremely complementary in this role. When they come to the forefront, Musselwhite uses his broad understanding of harmonica tone and structure to not overplay. Rather, his solos have a depth best suited and well-designed for the blues song being presented (“Blues Up The River”).

Musselwhite enjoys respectful percussion work, with Martin’s drumming cadences echoing the temperament of the song, sometimes quite subtle, and sometime slapping, but always pushing things forward. Bays’ bass work is equally restrained, and finds its value in its idyllic restraint.

Overall, the tenor of the whole of this Musselwhite collection is one of informality steeped in instrumental sparseness, providing a somewhat laidback sensibility, a framework that well summarizes Musselwhite’s life and times. This is a collection refreshing in its minimal production, and suggests Musselwhite alone with his thoughts, with only the final conclusions about experiences lived having relevance to him and being worthy of conveyance.

Most of the blues on the collection do not exceed three minutes; in fact, a number of blues here arrive well under that mark. However, the listener will be amazed at the messages put forth in that short a time span. Musselwhite is a genius of getting in and out of a song once its core message has been communicated. Front-to-back, this collection’s blues enrich with their substance, and that is best defined as the entirety of Musselwhite’s life.

There are many echoes for Musselwhite here, whether they be of Big Joe Williams (“Remembering Big Joe”) holding court outside of Chicago’s Jazz Record Mart on W. Grand Ave., or of blues mandolin great, Yank Rachell (“Hobo Blues”), or any of his countless other influences. What matters is that he has decided to enclose the total of his life in the blues within this astonishing collection.

Here, Musselwhite has indeed reached the summit of his recorded work. Without qualification, Mississippi Son is submitted here as highly essential.