Sara Martin – The Pioneering “Moanin’ Mama” Of Classic Female Blues Singers

Sometime in the very early 1980s, in a long-shuttered music store in South Bend, Indiana, I came across a copy of a 1970 LP collection entitled Ma Rainey & The Classic Blues Singers (CBS -52798), a superb 16-song compilation by some of the finest female blues singers from the classic era of the 1920s, a period defined as producing an early type of the music that was wildly all the rage, one that was a glorious combination of metropolitan auditorium music and the long-established common blues idiom, sung by women who did so with high passion and in a stylish approach.

Classic female blues is often also referred to as “Vaudeville Blues,” a nickname that attempts to reconcile the theatric component inherent in the music due to its prevalent use of smaller-scaled backing jazz outfits. Yet some of the finest classic female blues consists only of the singer, a piano player, and the internal sorrows the song’s lyrics depict.

I had only peripherally listened to this form of the blues up to the point of purchasing the LP, as my tastes, combined with naivety, at the time saw me diving into the works of more common blues names within my tight circle of fellow rabid blues fanatics, artists such as B.B. King, Freddie King, Buddy Guy, and Otis Rush on the contemporary side of things, with traditional blues artists such as Blind Boy Fuller, Robert Johnson, Blind Lemon Jefferson, and Charley Patton piquing our non-electric blues interests.

Ours was a blues that was testosterone-fueled, arising from a cadre of men bending strings in smokey, dank inner-city clubs, or dusty ramblers walking the southern U.S. highways or swinging up onto a train to ride the rails to some far-off street corner where spare change may come their way on the wrong side of town.

Looking back on the narrowness of me and my fellow collective’s understanding of the blues, I know that I now stand much better informed and more learned, yet a blush still comes to my cheeks as I grasp the extraordinary limitations of my blues intellect at that time. Now that there’s so many more miles in my blues rearview window, I can now laugh at my innocence without the inclusion of a feeling of shame.

The abovementioned CBS album and its significative effects on me were immediate and profound. Who were these women? When did they record, and for what labels? Are these full orchestras backing them or smaller aggregations? The blues melancholy is there, but why do I perceive it in a different manner? What is that sassy component I detect? So much was rolling around in my head as I played the LP over and over. To say that I was greatly intrigued is an understatement.

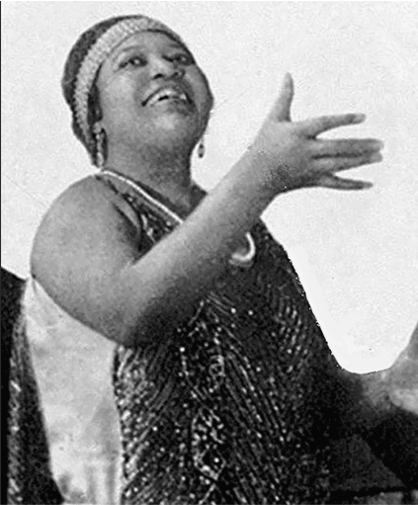

The “Classic Blues Singers” on the album included names completely foreign to me at the time, though with the benefit of decades of blues research now, their importance and prominence in my blues glossary is vastly more understood, validated, and respected. Nonetheless, who were Ma Rainey, Mamie Smith, Clara Smith, Martha Copeland, Eliza Brown, Sippie Wallace, Edith Wilson, Lillian Glinn, Bessie Smith, Mary Dixon, Liza Brown (Ozie McPherson), Ann Johnson, Victoria Spivery, Ida Cox, and Sara Martin. As I now am fully aware, these women all occupy substantial positions in the history of classic women blues singers and blues in general. But as I kept the LP on a steady rotation on my turntable, I was drawn specifically to the song “Black Hearse Blues,” Sara Martin’s contribution (and by the way, this tune could be rightfully perceived as the zenith of blues vocals). With one of my now favorite acoustic blues guitar players of all-time, Sylvester Weaver, providing support, Martin is actually credited for her vocals on the August, 1927 cut as Sally Roberts (she was also known to record as Margeret Johnson). The lyrics of the song are bleak, telling a story of past three departed paramours and how that black funeral hearse can’t have her number four man. It is blues drama of the highest order. This women blues singer also known as “The Famous Moanin’ Mama” was indeed a forlorn individual within this tune.

With March being Women’s History Month, it only seems appropriate that the life and rich capacities of Sara Martin should be briefly profiled as a way to celebrate all that women have done for the blues. And those contributions have been many.

The blues singer known as Sara Martin came into the world as Sara Dunn in mid-June, 1884 in Louisville, Kentucky, a great city along the Ohio River nearby the Indiana state border (research does not precisely piece together when Dunn adopted her stage name). Research has indicated that her parents were named William T. Dunn and Mary Katerine Pope. Often when I write about blues artists, I am stunned at how little information is documented about their earliest years; their musical influences, their initial performing opportunities, and the like. Unfortunately, this is also the case with Sara Martin, but enough research is available to piece together a fairly abundant timeline of her lifetime and musical career.

It is not unreasonable that Martin was influenced, as many blues artists have been, by the music she may have heard in church, but that supposition is without confirmation. But in listening to the profound, full vocal quality she possessed, one that was also rife with meaningful thoughtfulness and measured temperament, this writer would be careless in not stating his belief that elements of gospel lurk in Martin’s music.

In 1900 at the age of 16, Martin was already married, taking a man named Chritopher Wooden as her mate. However, a mere year later, he passed away. To put Martin’s relationship history into a brief synopsis, she was also married to Abe Burton (if Martin lost Burton to divorce or death, research does not readily indicate), and many years later at the time of her passing she was married to a man named Hayes B. Withers.

The southern U.S. auditorium performing (i.e. vaudeville) circuit was teeming in the years leading up to the beginning of World War I, and study shows that Martin was performing with these roaming pacts by 1915 when she was in her late twenties, her vocal skills more-than-sufficiently developed to do so. This outlet for Martin’s robust and moody vocals and ever-emerging stage presence provided her invaluable exposure across a broad swath of the southern states, along with building her self-confidence.

The U.S. record companies were paying close attention to what was happening at the time in the southern U.S. music-wise, and saw an opportunity to exploit it. “Race records,” as they were called, were clearly geared toward the Black population, and were wide in the genres represented, including blues, jazz, comedy, R&B, and gospel. These recordings made up the bulk of commercially produced records of U.S. Black artists. Labels that were big into “Race Music’ included OKeh, Vocalion, Paramount, and Victor, among others.

When the aforementioned Mama Smith’s “Crazy Blues,” a 1920 release on the OKeh label, hit the streets, it was excitedly received. This reworking of Perry Bradford’s 1918 song entitled “Harlem Blues” sold roughly 75,000 copies in one month, a phenomenally huge number for a record targeted to Blacks. As would be expected, every other record label was looking for their Mamie Smith to take advantage of the burgeoning “Race Music” market.

Remembering that Martin was born in 1884, at the age of 38 and with a lot of years performing on the vaudeville circuit behind her, she was signed by the OKeh label in 1922. Through her years of honing her craft, day after day, and night after night, on the southern U.S. performing trail, Martin had established her voice as a lush, big instrument, also forging a physical aura that overflowed with immaculate style and elegance. Much like today’s pop sensations, Martin was prone to change her extravagant regalia two, maybe three, times a night. In other words, she was poised to be a blues chanteuse of considerable attraction.

As great as 1922 was for Martin, 1923 was the year she really broke out recording-wise; OKeh released 18 of her records in that year alone. Though she was thought of as a blues singer, it would be more accurate to portray Martin as a singer who used more swaying, rhythmically danceable cadences. But when she leaned into a true blues number, that resonant, enveloping voice could convey the melancholy. There was no turning a deaf ear to her words and delivery.

Not only on records issued solely under her name, but as a singer on records where her vocals were featured complementing the work of other artists such as Sylvester Weaver, Clarence Williams, Sidney Bechet, and even King Oliver’s Band, it seemed as though whatever Martin touched became a top seller. All through the 1920s. Martin recorded for OKeh; a staggering amount of output. It seemed as though Martin was unfailingly producing astounding material. Another component of Martin’s popularity was the fact that the OKeh label spent liberally on promoting her; publicity efforts on her behalf were quite generous.

Due to her popularity (her standing as a stage performer was compelling everywhere she went), throughout the 1920’s she played on stages far and wide, with her musical competencies carrying her to points in the U.S. from the Midwest to the East Coast to the southern states. She even was featured internationally in certain Caribbean nations; such was her reputation.

So popular was Martin’s brand of jazz-infused swinging blues and her on-stage persona that she was invited to take part in a movie entitled Hello Bill, a production dating to 1929 that also featured another period entertainment icon, who like Martin, rode the wave of interest in Black performers, Bill Robinson a/k/a Bill “Bojangles” Robinson. At this point, it is said that Robinson was the highest compensated Black entertainer in the U.S., with that distinction carrying forward all the way to roughly the mid-1900s, such was his popularity. He passed away in 1949.

Moving forward, Martin’s success in Hello Bill, her appreciation for acting, and her ever-present musical skill set found her in another theater production, this one in 1930 entitled Darktown Scandals Review.

In 1932, Martin dedicated herself to her principal expertise of singing in aligning herself with Thomas Dorsey a/k/a “Georgia Tom” and “The Father Of Gospel Music”, the man who is credited with the authorship of thousands of blues and gospel songs, including such mainstays of the religious genre as “Take My Hand, Precious Lord” and “Peace In The Valley.” This phase of her career brought Martin full circle as a performer.

By this time in her life (being roughly 48 years of age), Martin had essentially seen and done it all in a fantastic music career that had seen her, like other classic women blues singers, blaze a trail for women in the entertainment industry. As one could imagine, constant life on the road is grueling, and for Martin, it was time to cease her wandering musical activities.

In her hometown of Louisville, Martin opened a nursing home, operating it as her new, hometown-based profession. She was active in her local church, and as one would expect, and became a member of the entity’s gospel choir. In essence, Martin went into the later part of her life in a more peaceful, relaxed manner, free from the inherent travails of the entertainment industry.

In May, 1955, Martin passed away from the ravages of a stroke. She was 71 years-old at the time of her passing. She is buried in Louisville Cemetery, with a magnificent headstone marking her final resting spot, a marker befitting her vast contributions to American music.

In context, it is interesting that despite the upward trajectory in the blues’ popularity in the early part of the 1900s being primarily propelled by women, after the great migration of southern Blacks into the major U.S. metropolitan areas post-WWII, the music became very patriarchal. Thinking of Chicago blues alone, for every Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Sonny Boy Williamson II, and Little Walter, maybe one female blues artist of note was receiving some semblance of notoriety. And, even before this period, in 1930s Chicago, much was the same. Names such as Sonny Boy Williamson I, Blind John Davis, and Tampa Red ruled the blues landscape. It was as if the genre gained its traction on the heels of the classic women singers and never looked back as male artists then carried the music forward.

Sure, there were the few prominent women blues stars early on such as Memphis Minnie and Etta James, among others, but the patriarchal control in the blues world was pronounced. Of course, the Vee-Jay Records label, one that produced many blues, gospel, jazz, and R&B songs throughout its heyday period in the 1950s-1960s was co-owned by Vivian Carter, but the reality was that the blues industry was top-heavy with male power.

As the blues industry plowed forward into the later part of the 1900s, women such as the gospel and blues singer and guitarist Sister Rosetta Tharpe, mighty blues vocalist Koko Taylor, harmonica player and singer Big Mama Thronton, rock/blues singer sensation Janis Joplin, cross-over great Bonnie Raitt, guitarist Rory Block, operatically-trained Valerie Wellington, and soul legend Aretha Franklin stirred things up more than a bit and wielded their broad skill sets to a new generation of blues and soul fans. The effect has been that contemporary blues figures such as the dynamic vocalist Shemekia Copeland, guitarist and singer Samantha Fish, powerful guitar player and singer Joanne Shaw Taylor, singers Demetria Taylor and Sheryl Youngblood, and multi-instrumentalist and vocalist Beth Hart, amidst others, can now find footing in the blues world.

And further ingress into the blues realm by women is witnessed by the venerable Chicago blues and jazz label, Delmark Records, being co-owned by Julia A. Miller. And certainly, the tireless work of women like Linda Cain whose great resource, the Chicago Blues Guide, is yet another indication of passionate female energies expended on behalf of the blues.

The work that these current-day women are doing on behalf of the blues, however, has its roots in the pioneering work of the classic women blues singers mentioned in this writing, artists such as Sara Martin who, to use a time-worn phrase, paid their dues in many ways to allow women to make the inroads into the music they have to-date.

Dipping one’s toes into what is becoming an ever-diminishing awareness and oh-so-vital period for the blues, that of the classic women blues singers, can grant a newfound appreciation for the blues’ roots, one that owes much to the women who caused so much excitement in the music so many years ago.

It is a journey worth taking.