Whistlin’ Alex Moore: A Diverse Texas Blues Piano Marvel Whose Contributions Deserve More Exposure

I believe the year was 1988 (unless my mind is deceiving me), and once again I was at the world’s largest free blues festival, The Chicago Blues Festival, an annual celebration of the blues held in the city’s magnificent Grant Park. Year after year, the festival had provided me so many opportunities to witness the blues of titans of the genre, and 1988 was certainly again not to disappoint. With blues and related genre artists including Otis Rush, Buddy Guy, Son Seals, Hank Ballard and the Midnighters, Etta James, Albert King, Fontella bass, Bobby Parker, Bobby “Blue Bland”, B.B. King, among many others on the bill, the 1988 festival was sure to be an incredible event.

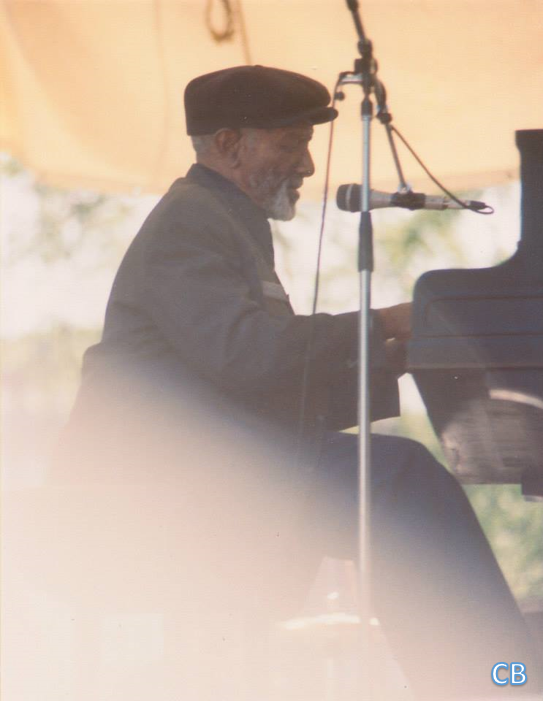

But, there was one particular series of performances to take place at the festival’s Front Porch Stage that I was particularly excited about. There was to be a parade of blues piano giants who were to appear, including west coast master, Charles Brown, and a trio of Texas piano greats who rarely traveled outside the state; the author of 1929’s “Blue Bloomer Blues”, Whistlin’ Alex Moore, barrelhouse artist, Grey Ghost, and the multi-faceted, Dr. Hepcat. My itinerary for a decent portion of the day was set, as I would claim a portion of the grass up-close to the Front Porch Stage so I could observe and bask in the music of these blues piano aces.

Wait! The preamble to this blues artist profile sounds suspiciously akin to one that appeared just a couple of weeks back on Dr. Hepcat. Why? Because it is the same first couple of paragraphs. In reflection upon that day in 1988 at the Chicago Blues Festival when I saw the awe-inspiring parade of blues piano geniuses, I now feel an intense imperative to also write about Whistlin’ Alex Moore!

While all four of these astounding blues pianists were awe-inspiring, I was especially curious as to what to expect from Whistlin’ Alex Moore. Certainly, his aforementioned 1929 recording of “Blue Bloomer Blues” has stood the proverbial test of time. However, Moore was no one trick pony, as he had a number of additional fine blues to his name; “They May Not Be My Toes”, “West Texas Woman”, “Ice Pick Blues”, “Heart Wrecked Blues”, “Come Back Baby’, “Bull Con Blues”, “Hard Hearted Woman”, “Across the Atlantic Ocean” and “Black Eyed Peas and Hog Jowls”. In addition to being a first-rate blues piano practitioner, he was an excellent vocalist, and per his stage name, was also known for his whistling. Needless to say, my curiosity was peaked. Especially years ago, when the ravages of time hadn’t yet depleted the ranks of early period blues artists, settling in for a performance by an obscure blues artist was a unique indulgence. I simply couldn’t wait for Moore to begin his set of blues piano mastery.

Alex Moore came into the world in Dallas, TX in the last year of the nineteenth century. His family left Dallas early in his life, but returned in a few years. During his youthful years, despite his family not owning a piano, he learned the instrument by watching others play. Due to his high interest in the instrument, he sought available pianos throughout his community upon which to practice. Also, during this early period of his life, Moore challenged himself to learn harmonica. In an attempt to round-out his skill set in an effort to become a full-blown entertainer, Moore learned tap dancing, while also discovering that he had a knack for whistling, a liking he used to great effect throughout his long musical career.

However, Moore’s piano interest didn’t fully consume him until he got into his teenage years. He did not sight-read music; rather, he played by ear. A turning point in Moore’s career in music came at the age of 16 when he performed on a radio station in Dallas. This degree of notoriety allowed Moore to begin to play piano for money in the various joints in Dallas.

Moore’s career was somewhat put on hold after his father passed away, and was called upon to work to support his family. At the age of 17, Moore went into the U.S. Army. After his stint in the service was complete, Moore continued to develop his piano skill set.

Moore’s initial musical development included a wide array of piano styles, including not only blues, but boogie woogie, stride (a jazz piano style), and strict ragtime. It was also during this creative, career-shaping period when Moore firmly secured his “Whistlin’” moniker due to a whistling sound he made as he performed on the piano.

The age of 30 proved fruitful for Moore. A field recording outfit for Columbia Records happened upon him, and a total of six songs were recorded and eventually released, though they did not sell in especially good numbers.

Once the Great Depression took hold, Moore’s musical career was halted until 1937 when Decca Records offered him a recording session. However, traction did not occur, and Moore continued to play in Texas, while also, at times, working as a hotel bellhop.

It would be another decade until Moore again recorded. In 1947, Moore laid-down a series of tracks, ten total, at a Dallas radio station. This session presented itself through the benevolence of Moore’s employer, a restaurant owner, but unfortunately, the cuts were not released until 42 years later. Another recording session presented itself in 1951 for the RPM/Kent imprint, but of the songs recorded with Smokey Hogg, a disappointing one was ever released.

Yet another nine years would pass before Moore had the opportunity to again record. By 1960, the folk and blues revival was flourishing, The story goes that the famed British music researcher, Paul Oliver, located Alex Moore close to his boyhood home, and made his awareness known to Arhoolie Records founder, Chris Strachwitz. Strachwitz convinced Moore to record, with the Arhoolie label releasing Alex Moore in 1961. This fine release was chock-full of Moore’s meld of musical influences and sense of never-ending extemporization. Moore’s unique aptitude for impulsive musical departures, peppered always with the blues as it roots, shone through on these recordings. Given that Moore was initially based in playing in the Texas joints, this should come as no surprise, as a piano player in those environments would need to keep the music going all night to satisfy the revelers. As on cue, Moore’s recordings also highlighted his somewhat adenoidal vocal quality with that characteristic harmonious whistle for which he was so well-known.

It is especially important to note that 12 additional cuts from the Arhoolie session were later released by the label, including ramblings by Moore about his earliest days plying his piano trade in the Texas establishments.

Due to the Arhoolie release, Moore was finally able to travel and perform outside of Texas, and he became a member of the 1969 American Blue Festival that visited Europe, which had the great added benefit of him being able to record two albums while there. One album featured Moore solely, In Europe, which was released by Arhoolie in 1970.

1987 was an important year for Moore, as he was the recipient of the National Heritage Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts. He was the first black Texan to be bestowed that high distinction.

Though achieving this higher level of awareness, Moore continued to play local, and only recording the one-off song sporadically. However, in 1988 at the age of 89, Moore recorded for Rounder Records, an outing entitled Wiggle Tale. It was a set recorded in-performance in a Dallas club. It was to be Moore’s final recording, as he passed away in very early 1989.

Never through his long musical career did Moore not work a day job of some sort; dishwasher, custodian, hotel porter, hauler, among other positions. It was as if music was not truly his profession, but a calling, a gift to be rolled-out at his whim to please not only himself but his fans.

I was one such enamored fan in 1988 as I sat in rapt attention throughout Moore’s amazing set at the Chicago Blues Festival. I look back on that day, and truly realize how very lucky I was to have witnessed the diverse, astounding blues talent of Whistlin’ Alex Moore. I still feel very fortunate all these years later.