Otis Rush: Ingenious Chicago Blues Guitarist Without Peer

Many years ago, when I was In Chicago for a banking conference, that familiar thirst began to creep into the forefront of my mind one Thursday, and as the day’s training sessions labored into the afternoon, my focus began to wane. All I could think about was the clock striking 5pm so I could escape for an evening of great Chicago food and blues.

After a quick shower to revive my blurred senses, I headed-out for dinner at one of my favored Chicago steakhouses; I believe it was Gibson’s on N. Rush St. After consuming more red meat and side dishes than any one person should attempt, it was time for me to begin my journey northward into the Chicago evening to find the blues that would satisfy my deep yearning for a dose of the music I hold most cherished.

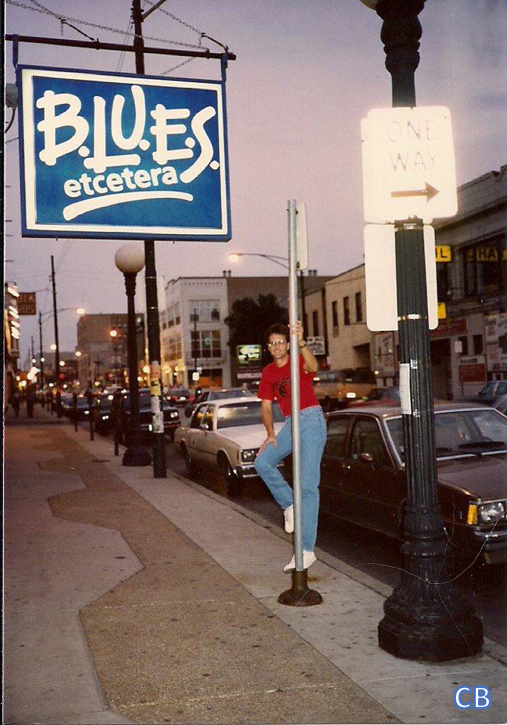

I took the Red Line “L” north, and when I disembarked at the Belmont station, I began my short walk in the cold night air toward my destination. Most of W. Belmont Ave. by this time of night was represented by small closed businesses, though, as in any major urban environment, there were still certain retailers operating into the nightfall hours. As I crossed onto the north side of W. Belmont Ave., I to this day distinctly remember peering down an alley across the street and observing a troupe of The Guardian Angels, representing the efforts of the non-profit international volunteer organization of unarmed crime prevention, patrolling the area. For some reason this provided me comfort and a sense of security as I walked my last couple of blocks to my destination.

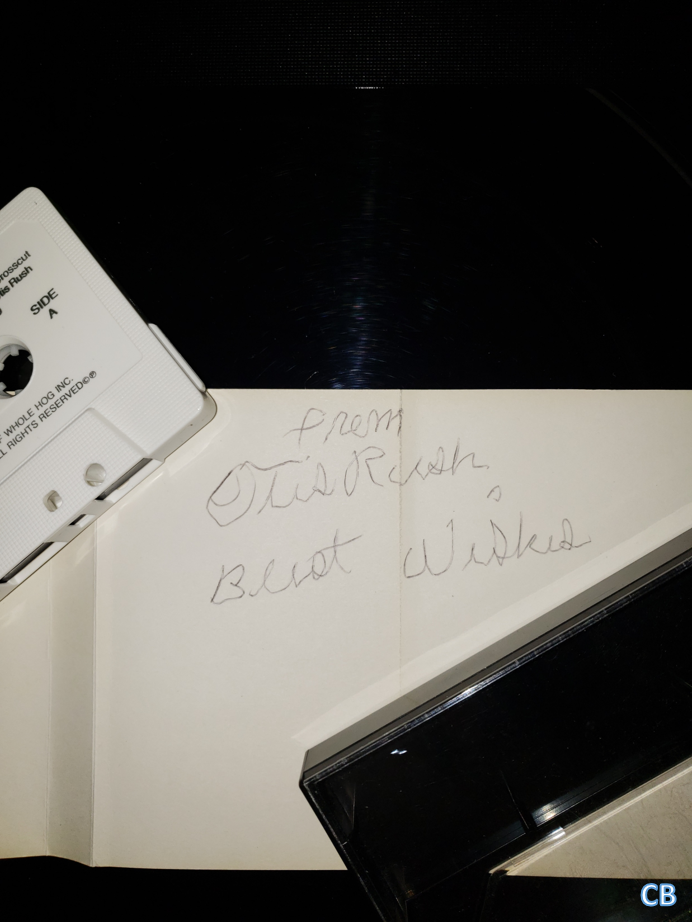

I reached B.L.U.E.S. etcetera in the 1100 block of W. Belmont Ave., and after paying my cover charge and getting a drink, I settled into a high-top table not far in front of the sound board. Being Thursday night, the collected crowd was thin, and it was an hour or so before show time. I had brought along a cassette tape hoping that I could get the evening’s legendary blues artist to autograph its liner for me, and I pulled it out of my coat pocket and sat it on the table so as not to forget to do so.

A few more patrons filtered into the club, and the venue’s energy began to feel a bit more enlivened. Roughly 45 minutes before the announced show time, the club’s front door was opened and braced ajar, and it was obvious that the musicians had arrived, as they began to bring their gear inside. One of the musicians, a bearded man who to this day I believe to have been Bob Riedy, made a general announcement into the club that he was seeking assistance in bringing a Hammond B3 organ into the venue. A group of us sprang into action, getting it through the door and hoisted onto the stage.

And then, the night’s blues star strolled in. If you were to ask me who my favorite bluesman of all-time is, I’d say, “Otis Rush.” The combination of Rush’s inventive blues guitar mastery, poignant vocal abilities, and mood chemistry long ago touched me in a way no other blues artist has ever done. Resplendent in his perfectly creased jeans and black leather belt with a large shiny buckle, black long-sleeve shirt, glossy black leather vest, perfectly situated black western hat, and gleaming gold chain and medallions, Rush cast an imposing stature. A noticeable buzz arose in the club, as those who were true blues fans realized that they were in the presence of one of the most influential guitar players, blues or otherwise, of all-time. Rush headed to the small private room behind the pool table for a bit, and as was his routine when a pool table was close by, when he emerged, he settled in for a couple of games of eight-ball. Those who knew Rush were aware that he shot a very good game of pool. I learned years ago not to engage certain bluesmen in a game of billiards, a lesson I absorbed after rightfully being separated from my money by bluesman Carlos Johnson at Rosa’s Lounge in Chicago one night.

The rest of the night was one of those performances when Rush was engaged, in-the-moment, and driven to entertain. He presented blues that were long parts of his “live” performing repertoire as if they were new, reaching and stretching to find new inventiveness in his fretboard meanderings, and seeking novel re-workings of blues tunes that he easily must have played thousands of times. Rush’s vocals were heated, as if he was reliving the emotional inputs that helped him shape his lyrics. His dynamics were impeccable, as he demanded of himself the tone, touch, and clarity, not only in his guitar mastery and his voice, but of the overall band experience. One would have thought that Rush was playing before thousands of eager blues fans at a major festival. This was one of those performances when Rush was in full engagement with the proceedings at-hand, and those who witnessed it probably speak about it to this day, as I do.

Between sets, I asked Rush for an autograph on my cassette liner, and he most graciously provided one. I also asked Rush for a photo, and again, he most amiably agreed to my request. I will never forget this particular experience of seeing and hearing Rush, because actually interacting with him was a true honor.

Rush, like many blues greats, was born in Mississippi, with his year of birth being 1934. And also like many blues artists, he grew-up working on a farm. While still a young boy, at age eight, he began to teach himself guitar. While still in his middle teens, again, like many of his blues peers, he made the move northward to Chicago, where he initially was motivated by the music of Chicago blues titan Muddy Waters. He was getting opportunities to play in the highly-competitive west and south side blues places, and when he eventually decided to start his first band, he booked himself under the name Little Otis.

Rush had a very unique way of guitar playing, as he was left-handed, yet he strung his guitars with the low E string at the bottom of the instrument, which was an approach that was, in essence, inverted from conventional guitar players. It was interesting to watch Rush pick his guitar, as he situated the small finger of his picking hand beneath the low E string. This technique allowed Rush to achieve a guitar sound unique to only himself.

Rush’s guitar work was also highly-inventive, almost in a jazz manner, as he always seemed to be experimenting in an attempt to find new constructions for his runs. Rush could take a single note or phrase and, in a way, try to coax himself into spinning fresh inventiveness into a passage. He constantly seemed to be experimenting and searching. Make no mistake; much of Rush’s guitar catalog is brimming with blues guitar standardizations that need not be tampered with, such as the incredibly haunting stanzas in “All Your Love (I Miss Loving)”. Therein lies the beauty in Rush’s guitar approach, in that his search for musical idealism seemed to convey his artistic integrity.

Rush’s vocals were highly- and achingly-impassioned, and the theater he is able to create through them is the very definition of “vividness”. His mournful cry at the beginning of “I Can’t Quit You Baby” aches with grief and regret. Rush’s ability to effectively use his formidable tenor voice to allow the listener to envision the stories behind his blues is the stuff of genius. His sung lamentations and celebrations were sincere, as his voice continually arose to the occasion required to paint an illustrative portrait of his blues premise.

Rush’s big break came at the age of 22, when he signed with Chicago’s Cobra Records. Over the course of three years (1956-1958), Rush recorded some of the most important blues in the modern vein, songs that were tormenting masterworks, bursting with emotional drama, cuts that seared and tore at the heart of the human condition. These blues were Rush’s vision of the blues as it continued its assault into an electric time ahead. These 20 Cobra label cuts went on to be covered by many of rock-n-roll’s most recognized bands and artists, including Led Zeppelin and Eric Clapton. Cobra went out-of-business in 1959, and Rush was again seeking a recording contract.

Rush signed with the famed Chess Records label in 1960, an arrangement that allowed him to record eight blues, of which four of the cuts were released on two singles. Six of the blues eventually made their way onto a 1969 album that was a collection with songs recorded by fellow bluesman Albert King. Rush also recorded for the Duke label in 1962; however, just one single was released. He also recorded for Vanguard in 1965 for a compilation produced by Sam Charters. During this period, Rush toured the U.S., along with Europe, as part of the famed American Folk Blues Festival package tours. In 1969, Rush traveled to Muscle Shoals, AL to record a new collection that was released on the Cotillion label. This was an interesting foray for Rush, as the production sound on this recording was more in a soul/rock-n-roll vein.

In 1971, Rush recorded what many consider to be his finest post-Cobra label recordings, an album entitled Right Place, Wrong Time. But like much of Rush’s recording efforts, its labors were great and lengthy. Capitol Records was to release the album, but chose not to do so. It was five years removed when Rush bought the session’s masters, with the outing finally seeing the light of day in 1976. Many consider this album to be the finest that Rush ever produced.

During the 1970s, Rush continued to record and tour, with albums appearing on the Sonet and Delmark labels adding to his recorded output. Dismayed by the lack of overall success and dwindling recording opportunities, Rush retreated from the blues music business in the late 1970s.

It wasn’t until Rush re-emerged in the mid-1980s, touring behind a new “live” album that was recorded at the famous San Francisco Blues Festival, that original fans and new devotees were able to experience the blues magic of Otis Rush. In the ensuing years, Rush continued club and festival work, and in 1994, finally recorded another studio album. Until that point, it had been roughly 16 years since his last album. He followed-up with another studio effort in 1998, Any Place I’m Goin’, a collection that allowed Rush to earn his first Grammy honor.

All seemed like it was going well for Rush, as he continued to tour. But in 2003, he suffered a debilitating stroke, and was gone from the blues music arena. Wholly 13 years later at the 2016 Chicago Blues festival, Rush was feted by fellow blues musicians and Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel, who declared Otis Rush Day in Chicago. Strikingly frail and thin in his wheelchair, Rush was obviously greatly moved by the energies on his behalf, and in a broken, weak voice, declared from the Petrillo Bandstand in Grant Park, “Let me hear you say ‘yeah’!” It was the last time that Rush was seen in-person before his legions of admirers, and he passed away two years later as a result of complications from the stroke.

Befitting the major blues influence Rush was, he earned a spot in the Blues Hall Of Fame, achieved an accolade form Rolling Stone Magazine for being one of the most important guitarists ever, and was a Lifetime Achievement Award recipient from the Jazz Foundation Of America for the totality of his music and its inspirations thereof.

Like any other artist in a performance field, the fact must be recognized that on a given night, no matter the talent level or years in a chosen craft, there are shows that are better than others, for whatever the reason or reasons. Artistic performers are, after all, humans, subject to the same pressures and stimuli as anyone else. And Rush, like any other blues musician, surely had those performances when he, to whatever degree, “phoned it in”. However, on that night I reminisced about at the beginning of this writing, when Rush was in full creative bloom, the results were stirring, and blues art of the highest categorization. Otis Rush was richly one of the most important modern electric blues artists in the history of the genre, and his inspirations continue in guitarists today, blues and otherwise, the world over.