Recommended Blues Recording

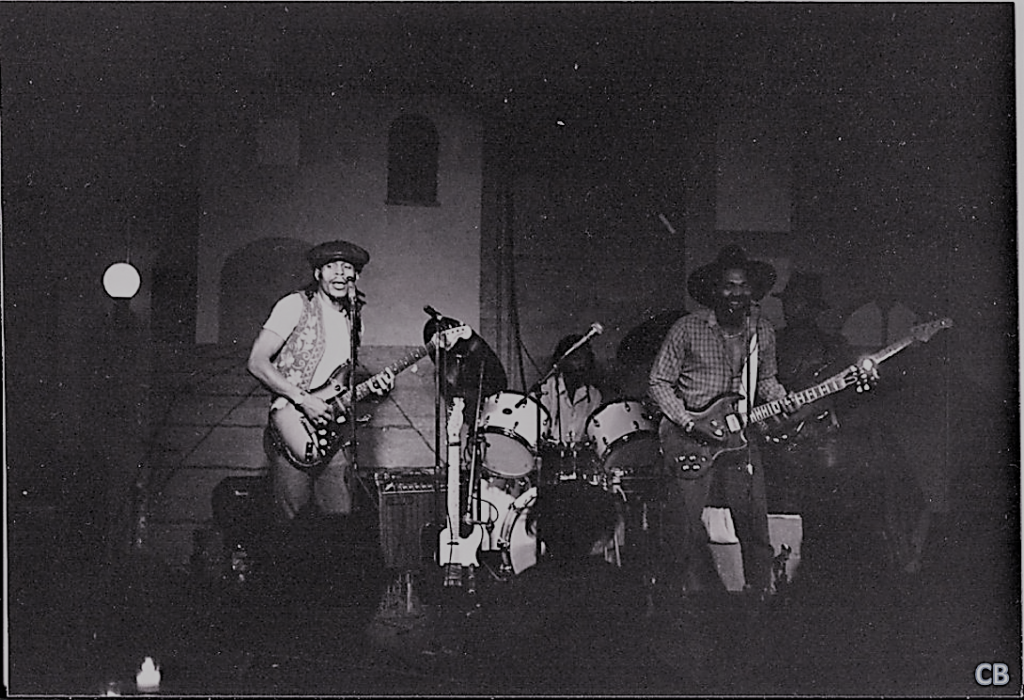

Big Daddy Kinsey & the Kinsey Report – Modern Urban Blues With Multiple Influences

Big Daddy Kinsey & the Kinsey Report – Bad Situation – Rooster Blues Records R2620

Back when my friends and I were new to the blues, everything about the music seemed so foreign; exotic, really. Growing-up in north central IN was, for the most of us, a very conservative upbringing. As young people in the 1960s, TVs had three channels, and programs were presented in black and white. Dads worked, and mothers managed the homes. Dinners were sit-down affairs where children were best seen and not heard, and evenings were spent watching safe, morally decent programming (at least that’s how society concluded it at the time).

Music on TV was limited to The Lawrence Welk Show, The Andy Williams Show, and The Dean Martin Variety Show, among other similar fare. Oh, sure, Woodstock happened in 1969, but that type of noise was reserved for long-haired counter-culture commie pinko radicals.

The advent of the 1970s saw us all aging into our fervent appreciation for rock music, and since rock titans such as Led Zeppelin, The Rolling Stones, Black Sabbath, Queen, and so many other rock giants were endlessly touring, for a ticket price of $6 and some gas at $.61 a gallon, we spent many evenings traversing the Midwest attending concerts and festivals.

Still, though, it was a very narrow life we were living, as we chose to cloister ourselves with our like-minded and like-reared friends during our experiences and travels, never really facing any sort of real cultural diversity.

So, when those of us who chose the blues as our chosen musical odyssey, we reveled in this mysterious new musical form that took us out of our sheltered Midwestern communities and introduced us not only to a new art form that seemed to speak directly to us, but to an assembly of individuals whose lives were fashioned by incredibly different societal inputs.

Such has been the case with my association with the blues over all these years, as I study the music, and attempt to place it within a framework of understanding that allows me a greater understanding of all its roots and styles, given that my background differs so appreciatively from those who lived and made the music.

As my cohort first began to gather the blues in our heads and hearts, we were driven toward the more rural blues stylings, and then to the post-war Chicago masters of the blues sphere. These forms of the blues represented the music at its most basic, and then, still at its most basic, but amplified in an attempt to be heard in the untold number of urban black listening places. Nonetheless, the music remained rather straightforward, with only the volume of the urban blues band bearing amped-up variations of the country blues that existed before the great black migration northward.

As such, it came as a great shock when our continuing interest in the music led us to a more stirring, startling, and mystifying version of the blues, one where various musical influences, instruments, horns, and guest artists abounded. This was not the classic two guitar, bass, piano, drum, and harmonica style churning-out the classic Chicago “lump de lump” blues. Yes, it still was an assembly including guitars, drums, bass, piano, and harmonica. But added to the mix were perhaps influences gleaned from band members having been ensconced in other musical forms, varied horn sections including trombone, tenor sax, and trumpet, the use of electric pianos and organs, electronic percussion, and a multitude of guest artists. Clearly, we had stumbled upon a new kind of blues that continued our education into its essence.

Hailing from Gary, IN, a brief 66 miles west from my hometown in the South Bend area, the Kinsey family, led at one time by Lester “Big Daddy Kinsey”, continued that city’s great blues tradition. At one time, blues artists such as John and Grace Brim, Johnny Littlejohn, and Albert King, called Gary home. Plus, being only 31 miles east of Chicago, Chicago blues legends such as Muddy Waters frequently played the clubs and taverns there. Gary is a city historically musically rich community, with no less than The Jacksons calling the area the place of their births.

Big Daddy Kinsey hailed from Mississippi, and arrived in Gary in 1944. He began playing guitar before coming north, and after working in one of Gary’s steel mills, and then undertaking a military stint, he permanently settled in Gary, marrying and nurturing a family. His early blues work included stretches with local bands. His first two sons were born in 1952 and 1953, and they joined a band led by their father while still quite young. A third son was born in 1963, culminating in a family band that toured the South and the Midwest.

Big Daddy Kinsey was proficient on guitar (including slide guitar) and harmonica, and possessed a strong, commanding voice. Regrading Big Daddy Kinsey’s son, they sought their musical sensibilities in differing manners. Donald Kinsey initially worked with Albert King for a stretch, and he and his brother, Ralph, also plied their musical energies in a rock band for a bit. Through this foray into rock music, both Donald and Ralph were awakened to reggae music and its unique rhythms; they absorbed these into their individual blues outlines. Donald Kinsey actually toured and recorded with both Bob Marley and Peter Tosh. Once the boys returned to the family unit, combined with Big Daddy Kinsey’s hard blues background, and the changes occurring within blues for young blacks, the stage was set for the whole of the Kinseys musical influences to converge onto Big Daddy Kinsey’s first album under his own name. And it was a modern urban blues excursion.

Recorded in 1984 at three studios in the greater Chicago area, and released on Rooster Blues Records in 1985, Bad Situation brought together the new urban blues textures via the use of additional instruments and guest artists, producing a recording that represented a new blues form, one layered in sounds and individual inputs quite outside traditional blues boundaries.

Besides Big Daddy Kinsey offering his convincing vocals, guitar, and harmonica skills, this collection offers Donald Kinsey on guitar and electronic percussion, Ralph Kinsey providing percussion work, including bongos, and Kenneth Kinsey on bass, while a host of guests lend their support. Floyd Johnson offers his work on organ, Nate Armstrong pitches in on harmonica, famed Muddy Waters pianist, Pinetop Perkins, plays keyboards on five cuts, and Chicago harmonicist Billy Branch lends support on two selections. Additionally, Frankie Hill plays piano and electric piano on three songs, with Bill McFarland, Henri Ford, and Paul Howard supplying trombone, sax, and trumpet work, respectively. In addition, Donald Kinsey, Janis Patton, Robin Robinson, and Valerie Wellington provide background vocals.

As indicated, the variety of inputs here are many, but they represent the more urban blues framework and texture that was a departure from traditional Chicago blues. Of course, this release highlights Big Daddy Kinsey’s authoritative vocals, brimming with world-wise knowledge and wisdom (but with stylized vocals from the backing vocalists), his economical, yet effective guitar excursions, and more-than-passable harmonica surveys. This is his show, and two cuts in particular, Nuclear War Blues” and “Tribute To Muddy” showcase Big Daddy Kinsey in topical and reflective modes that work very well. When one hears Kinsey sing, his resolute technique leaves no room for confusion as to the message being put across.

Donald Kinsey’s guitar work is substantial, searing and swirling, while Kenneth Kinsey’s bass efforts are intelligently delivered. Ralph Kinsey’s percussion work keeps a firm solidity to the entirety of the proceedings.

The assembled horns swing and swoop, layering a textured sophistication to the outing. They never intrude, only adding levels of tension, and degrees of metropolitan machinations.

On his selections, Branch’s harmonica stays in more of a traditional strain, showing that despite the modernistic attitude on display here, he is able to adapt his skill set to ideally suit the framework.

Perkins’ piano work is befitting his advanced billing and pedigree, tasteful and always appropriate, offering the required touch, feel, and degrees of restraint or boldness required.

The whole of this CD presents that modernism the blues undertook when traditional frameworks were introduced to urban sensibilities. To those of us who were cutting our chops on more old-style blues, it was a pleasing slap in the face, but a slap in the face, nonetheless.

It’s interesting how, even though this is not proffered by me to be an essential blues recording, I have written to considerable length about it. What it lacks in essentialness it dispenses in a blues framework that excites the senses and forces one to see the blues anew.

Not indispensable, but highly-endorsed, however. You will be moved!