Essential Blues Recording

Hound Dog Taylor and the HouseRockers – Raw, Rough, And Gritty Chicago Blues

Hound Dog Taylor and the HouseRockers – Raw, Rough, And Gritty Chicago Blues

Hound Dog Taylor and the HouseRockers – Hound Dog Taylor and the HouseRockers – Alligator ALCD 4701

The challenge when reviewing a blues collection that is virtually universally recognized as one of the finest modern Chicago blues releases is finding something new to say. Like an old friend, you don’t have to reinvent the past; you let the body of the collective times convey all the important things. What is important will easily surface. Such certainly was the case when revisiting this 1971 gem.

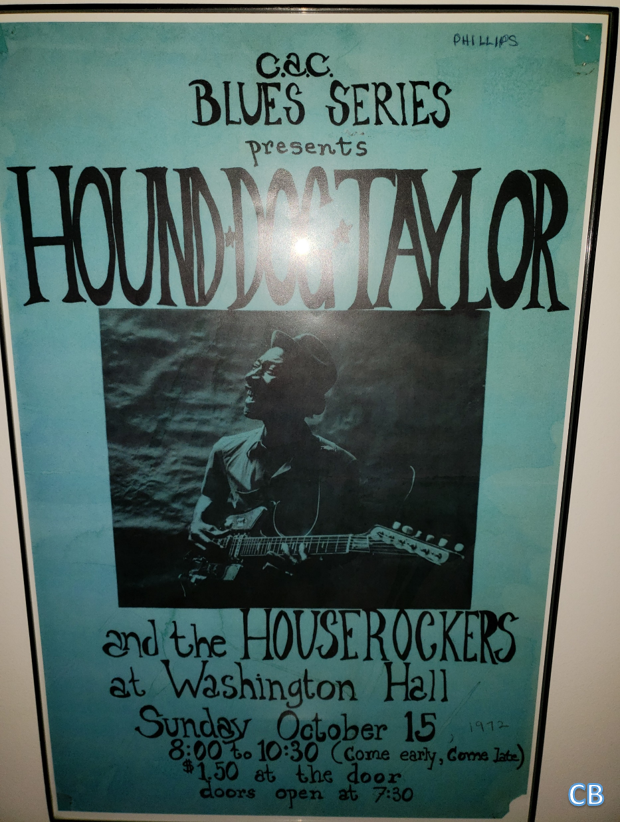

As blues lore goes, Alligator Records’ founder, Bruce Iglauer, was biding his time working for the legendary Bob Koester as a shipping clerk for Delmark Records. Fueled by experiencing Taylor’s brand of blues at Florence’s Lounge on S. Shields in Chicago in 1970, Iglauer petitioned Koester to consider chronicling his work, but Koester wouldn’t do it. It was not a recording project that Koester wanted to undertake at the time. Luckily for the blues, and blues fans everywhere, Iglauer turned to $2,500 of inheritance funds to begin what is now a 51-year journey with Alligator Records, deciding that Hound Dog Taylor and the HouseRockers would be the first blues band he and his fledgling label recorded.

Without going into Taylor’s background (that is best left to a broader writing), over the course of two evenings, Taylor’s first Alligator release was recorded, and now in retrospect, only blues of this intensity and insistency could be captured without the necessity of numerous takes and overdubs. This is raw and unvarnished Chicago blues from a group who had plied their trade in the dusky joints and corners of Chicago’s blues realm.

Blues of the sort found here is meant to be played loud, whether in-performance or on a stereo. There is an enthusiasm and genuineness here representative of the totality of Taylor’s aggregation, men driven to dispense with sounds mirroring the intensity, dangerousness, and pressures of the urban Chicago black experience. Taylor’s blues is simultaneously good-time party music racing with abandon, creating a racket that was commanded by the proceedings at-hand, while also being able to reach way down into the belly of the bluest blues to convey the agony of personal loss, betrayal, or unfortunate occurrences. There is nothing here that is like the “pretty” blues presented by blues-oriented orchestras with dignified singers, nor is there anything gentle, like a subtly reflective tune of wistful melancholy.

Taylor’s distorted, fuzz-laden guitar work was able to create a curtain of maniacally contorted sound that in an instant could segue from single stinging notes to a ripping, tearing, slashing, and sliding cascade of frenzied tones. His excursions cut and seared, propelling the emotional content of his blues bluntly forward in a manner as to leave no doubt as to the blues message being expressed. Assisting Taylor articulate his guitar reverberations was his choice of cheap Japanese Teisco guitars, instruments known for curious body profiles and features, including four sets of pickups, plus a variety of tonal control switches and options, that provided many sonic choices for the artist using one. They could be purchased at Sears & Roebuck stores, and more than likely, Taylor bought his there.

Taylor’s voice is celebratory, sorrowful, and encouraging on this release, depending upon the blues tale being relived. Taylor accepts his role and duty as the blues song’s tale commander, and without vagary, convinces the listener of the circumstances outlined in each of his tunes. His voice rises and falls in emotional output as compelled by the song’s outline and purpose. Taylor doesn’t sing at people; rather, he sings to them, as is speaking directly one-on-one with them.

Brewer Phillips does more than merely play second guitar to Taylor’s primary lead guitar responsibilities. First, there is no bass guitar in Taylor’s trio. Phillips’ underpins the blues here with a noticeable solidification of the low-end. His deeper runs create drama and backdrop; they growl. With Taylor’s guitar seeming often at the edge of mania, Phillips’ bedrock efforts keep thigs from going off the rails. His guitar mastery is the glue and counterpoint holding the entirety of Taylor’s blues work together. However, when Phillips steps-out on his two instrumental excursions here, his lead designs thrill and create a hysteria that is blues of the grandest classification.

Ted Harvey’s percussion work may seem elemental at first listen until the listener realizes its propulsive structure. It may even seem busy, but in a good way. Harvey’s drumming propels the band’s visions toward their desired ends with disciplined determination; never over-the-top, but positively gazing over the edge in a managed commotion of pounding collaboration.

The perfect cliché to apply here is, “They just don’t make ‘em like this anymore.” For a very brief period, Hound Dog Taylor and the HouseRockers emerged from the small blues joints in Chicago to tour the country and overseas, eliciting joy from established blues fans, and making new ones along their travels. Taylor’s blues was of an unpolished variety; sweaty and gritty. However, even a diamond-in-the-rough is still a diamond.

If you’re serious about your blues collection, you need this one on your shelf!