Artist Spotlight

Barrelhouse Chuck – Chicago Blues Piano Phenomenon

This blues artist spotlight has a duality for me that makes writing it very difficult. On the one hand, I miss my friend, and blues piano master, Barrelhouse Chuck (born Harvey Charles Goering), so very much. On the other hand, I got to know and gain the trust and friendship of this marvelous talent and person, and witness his genius firsthand many times. There simply cannot, and will not, be another blues story like Barrelhouse Chuck’s. He was a phenomenon gone way exceedingly too soon.

It’s been roughly five and one-half years now that Chuck’s been gone. It just doesn’t seem possible. We all knew that Chuck was sick, suffering with prostate cancer, and was declining. When I received word that Chuck had passed, one of the most difficult things I ever had to do was contact then-Chicago Tribune music critic, Howard Reich, to inform him of Chuck’s demise. Reich and I had been in contact for a couple of days prior, and it was surreal to inform him that one of the best Chicago blues piano musicians ever was no longer in distress. The finality of it still gives me pause after all this time.

Chuck was an ever-present fixture in my hometown area, primarily plying his blues piano skills at Mishawaka, IN’s Midway Tavern & Dancehall, a legendary blues venue. If I close my eyes and reminisce about his shows there, I can see him at that old upright piano against the club’s east wall, providing a tutorial of a blues craft that is slowly fading into obscurity; blues piano mastery.

Whether Chuck was percussively banging chords with both hands, rolling a dark chord progression with his left hand while his right hand provided the melodic counterpoint, or beating out a fast-paced boogie, he did so with equal passion and reverence. Chuck never lowered his performance standards; he played each of his blues as if it would be his last chance to do so.

But Chuck was not all about the piano skill set he possessed, no matter how authentic and complete they were. No, Chuck’s blues vocals were likewise compelling. Chuck’s background and tutelage by the blues’ most legendary artists similarly assisted him in crafting his lyrical style, one that was part declamatory, a la Sunnyland Slim, swaggering and vaunting, like Big Moose Walker, highly-rhythmic, like the music of one of his greatest mentors, Little Brother Montgomery, or dark and ominous, akin to another of his blues heroes, Memphis Slim.

Chuck was born in Worthington, OH, and as his widow, Betsy Goering described, “…he was a half Cherokee, half French-Canadian orphan” who was adopted by “…straightforward, very kind, Mennonite parents.” Chuck’s first musical pursuit was the drums, and he learned how to play them at age six. By this time, Chuck’s family had moved to north central Florida, settling in Gainesville. However, Chuck’s introduction to the blues happened when he found a picture of Muddy Waters in a book. Chuck’s curiosity was stoked, and he set out to learn about Waters and his music. This proved to be a pivotal period in Chuck’s life, as he began to listen, and more importantly, study the blues. Also at this time, Chuck switched his musical preference to piano, and began teaching himself piano by absorbing blues piano techniques by listening to uncountable hours of blues records.

Chuck’s continuing fascination with blues piano saw him form a number of blues bands during his teenage years. Another important part of Chuck’s early blues piano development was very interesting and unique. He followed Chicago blues legend Muddy Waters around the south, often arriving at the show site before the band got there, just so he could be assured that he could again make contact with Pinetop Perkins, Waters’ piano player, and gain access to the band and the show. In this way, he could study Perkins’ playing and pick his mind about blues piano, getting what was an early indoctrination into a working blues band’s dynamics. Due to Chuck’s fervor to follow Waters and his band, the group all knew him and accepted him into their circle, often inviting him to breakfast with them after the shows were over in the early morning hours.

In 1979, at the age of 21, Chuck did the remarkable; he drove24 hours straight from Florida to Chicago’s north side to B.L.U.E.S., the famed north side blues club, to meet Chicago blues piano powerhouse Sunnyland Slim. The story goes that when arriving at the club, Chuck walked right up to Slim and introduced himself, indicating his non-stop trip to connect with him. This began a roughly 16-year period of deep friendship and mentorship with Slim that began Chuck’s internship into the Chicago blues scene.

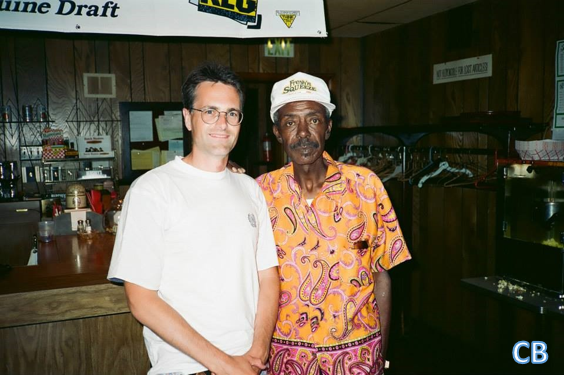

Anyone who was fortunate enough to gain’s Chuck’s friendship and trust knows he was an achingly authentic person. He was humble and kind, helpful beyond belief, and highly-respectful. In a circle such as the tight Chicago blues realm where suspicions run high and ego can detract, Chuck’s kind nature allowed him to become very close friends and a trusted individual within the congregation of blues piano royalty who were still alive, residing in Chicago, and still able to play. Chuck, through Slim, was brought into the worlds of Little Brother Montgomery, Blind John Davis, Big Moose Walker, Pinetop Perkins, Detroit Jr., the aforementioned Slim, Lafayette Leake, Erwin Helfer (with whom Chuck established a deep lifelong friendship), and many other blues piano greats.

Chuck was invited into their homes, learned from them, traveled with them, watched and listened as they performed together, and performed with them. His bonds with these men were deep, and in fact, he acted as a caregiver to Montgomery right up until his death.

Chuck continued to study blues, and also made other countless acquaintances throughout the Chicago blues scene. Floyd Jones, Jimmy Rogers, Eddie Taylor, Otis Rush, Buddy Guy, Otis “Big Smokey” Smothers, S.P. Leary, Hip Linkchain, and many others, allowed Chuck into their worlds and provided friendship and guidance.

There wasn’t anyone on the Chicago scene or who had been important in the city that Chuck hadn’t met, or played with, at some time or another; Johnny Shines, Willie Johnson, Billy Boy Arnold, Hubert Sumlin, Willie Kent, Billy Flynn, Louis Myers, Dave Myers, James Cotton, Steve Freund, Willie “Big Eyes” Smith, Nick Moss, Jody Williams, Honeyboy Edwards, Carey Bell, Snooky Pryor, Jimmy Johnson, Bob Stroger, Hubert Sumlin, along with so many others.

And, Chuck was known and revered for his blues piano work by the likes of national names such as B.B. King, Eric Clapton, Keith Richards, Billy Gibbons, Kim Wilson, Rick Estrin, Junior Brown, James Harman, Paul Oscher, Jerry Portnoy, and again, by a whole host of others.

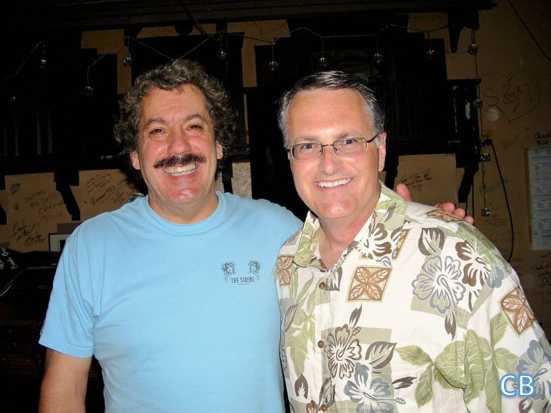

And quite uniquely, Chuck formed a strong bond in the South Bend-Mishawka, IN area by aligning himself with local blues vocalist and harmonica ace, Tom Moore. Moore was able to introduce Chuck to the owner of The Midway Tavern & Dancehall, a venue he played many times either solo, with his own band, or with area favorite blues band, Little Frank & The Premiers, a group fronted by Moore. Given the club’s close proximity to Chuck’s home just outside of Chicago, Chuck enjoyed the ability the relatively short drive to the club and back home again.

Chuck’s first recording came out in 1999 on the Blue Loon label, and over the years, he released many fine collections, 17 in total. Many of his works were released on his Viola Records label, and a number were provided by The Sirens Records label. He also had on collection issued on the Severn label, a work with Mud Morganfield and Kim Wilson. Chuck was also a guest on numerous recordings of other blues artists and groups, such as Nick Moss and Sweden’s Trickbag.

Chuck’s piano mastery was known worldwide, and due to this, he was often in-demand for group and solo work overseas.

Chuck was an indefatigable proponent of the blues. Whenever Chuck performed, was interviewed, or spoke on-on-one, he always paid homage to those blues piano players and blues artists who came before him. Especially Leroy Carr, a blues piano artist who Chuck held in the highest esteem, equating his influence and talents to no one less than Delta blues guitar legend, Robert Johnson. Chuck’s reverence for Carr was great.

Chuck also had a museum-worthy collection of blues articles in his home that was awe-inspiring. The scope of Chuck’s blues collection cannot be put into words. Show posters and handbills, photos, autographs, recordings, and all other manner of blues memorabilia on a scale as to be considered immense covered every square inch of the space that was bursting at the seams.

By the way, Chuck loved Boston Terriers, and the number of photos he had of his pooches was staggering. Chuck’s was a kind soul.

Latter-day efforts by Chuck found him working with Nick Moss (who paid tribute to Chuck on his latest CD on a song entitled “He Walked With Giants (Ode To Barrelhouse)”, and as a key member of Kim Wilson’s Blues All-Stars, with whom he traveled coast-to-coast providing that ideal mix of keyboard wizardry Wilson was seeking in his star-studded group, one that included Larry “The Mole” Taylor or Randy Burmudes playing bass, Billy Flynn and South Bend, IN-based Little Frank Krakowski offering their strong guitar skills, Richard Innes keeping time on drums, and Wilson singing and providing his splendid harmonica abilities.

Chuck also kept regular Chicago work, and in his final years, could be found working at Barrelhouse Flat on N. Lincoln Ave. Chuck was also involved in the recording of the soundtrack for the major-release movie Cadillac Records, and as part of the Howlin’ For Hubert concert at New York’s famed Apollo Theater.

I remember one Saturday afternoon working in my home garage when my phone rang. It was Chuck. He was driving from his home just outside of Chicago to my hometown for a show. I was showered with Chuck’s deep words of friendship, and humbled by his overwhelming me with the kindness of his sentiments. If you knew Chuck, you knew that this sort of conversation was genuine. I will never forget that meaningful conversation.

There is a blues song, “Mother Earth”, a 1951 composition by bluesman, Memphis Slim, that I just loved to hear Chuck perform. Yes, it’s a somewhat dark song in context, but when Chuck performed it, my realization that I was in the company of blue royalty was confirmed. Chuck was not steeped in the past for the sake of trying to sell a false sense of authenticity; no, his reverence and respect for those blues artists who came before him paved the way for his lifelong ability to pursue his passion as his true life’s calling, and he repaid the debt owed through giving each blues its proper due.

Erwin Helfer is still alive in Chicago, but is now 86 years old. Someday, Helfer will be gone. And then what? Who carries on the Chicago blues piano tradition? Chuck should still be here. At 56, he left us so early. I miss Chuck. I also miss the hearing the echoes of the masters whenever he would play, but as importantly, I miss Chuck’s unique confluence of blues inputs that digested itself into his own unique blues piano stew.