Recommended Blues Recording

J.B. Hutto & His Hawks - Modern Blues At Its Raucous Best

J.B. Hutto & His Hawks – Hawk Squat – Delmark Records DE 617

A racket. A commotion. A ruckus. Pick a noun, but when J.B. Hutto took the stage, his contagious blend of searing, slashing, and gnashing guitar work turned whatever room he was playing into a palace of volcanic blues slide guitar ecstasy. Much like Magic Slim, Jimmy Dawkins, and Hound Dog Taylor, among other modern bluesmen, Hutto’s delivery was an emotional and sonic overload to be reveled in and appreciated for its simplistic bombast.

Hutto’s was not “pretty” blues, such as that of the artists who featured full horn sections, swinging rhythms, and soulful, clean vocals. No, Hutto’s blues were strong, booming, and infused with the urgency and pressures of the daily black realities of Chicago’s south side. There were no rainbows and blue skies in Hutto’s blues, just the tearing heartaches and pains that led to deep wounds inflicted by day-to-day life in the ghetto.

Recorded over a number of sessions between 1966-1968 in Chicago, Hawk Squat was Delmark’s second modern blues release, following Junior Wells’ ground-break Hoodoo Man Blues. This period for Delmark was a turning point in that the label had historically released albums by bluesmen who had roots to a much earlier time in blues history. And as we all know, Delmark went on to release more contemporary blues albums by artists who remain vital to the core of modern Chicago blues including Magic Sam, Jimmy Dawkins, Jimmy Johnson, Luther Allison, Mighty Joe Young, Otis Rush, among many others. That dedication carries forward into today.

The blues was being discovered and emulated by young British bands and youths in the mid-to-late 1960s, and as we’ve touched upon previously, this led to new notoriety for Chicago’s blues artists. Blues was influencing rock and roll. And, the music was still being demanded in the south and west side clubs by older blacks who grew-up with the blues from its beginnings as a relatively solo from of music to the loud ensemble art form it became that was demanded by the noise of Chicago’s taverns. The music was amplified, loud, and forceful, matching the tensions and pressures of everyday life in black Chicago. A modern blues was called for in these environs. Not far down the road were the 1970s, a period when younger blacks continued to turn away from the blues, initially because of heritage issues, but then because of the advent of soul music, and eventually, disco.

Nonetheless, Delmark’s patriarch, Bob Koester, knew from his frequent expeditions into Chicago’s south and west side blues scenes that the blues was continuing to evolve into this driving, sonically rough brand of music, and he was determined to capture its ferocity. Koester speaks to first seeing Hutto at Turner’s, a small tavern on the southside somewhere around 1962-1963, and being seized by the intensity of his brand of blues.

At the time of these recordings, Hutto was living in a south suburban enclave of the greater Chicago area, but he was still frequently playing Turner’s. In fact, it is said that Hutto more or less made Turner’s his home base for roughly a decade.

There is a great scene in the 1972 film Chicago Blues that features J.B. Hutto in some south or west side tavern that captures both Hutto’s casual nature, the informality of the evening, and yet, the sheer strength of his performance. Typical to his Turner’s shows, the film’s band includes Hutto, a bass player, and a drummer. Hutto brays his blues tale from an improvised stage area in the tavern, while his band churns and chugs behind him. A young lady approaches Hutto as he is performing to whisper something in his ear, lending further credence to the informal nature of the black blues musical experience of the time. It was a personal experience in the south and west side taverns, yet Hutto’s blues was powerful, despite casualness of the venue and its patrons.

Hutto is also seen blowing-out candles on his birthday cake. This 59-minute Chicago blues documentary is a requirement for anyone interested in modern Chicago blues in general, and Hutto, in particular. It will assist in providing perspective on the Chicago blues scene of the time.

Delmark surrounded Hutto on Hawk Squat with a number of highly-skilled individuals, most of which who work to the benefit of the end result. Sunnyland Slim was brought onboard to provided his piano and organ skills, and they work to great effect. Slim’s piano work in not hidden in the background, heard as some tinkling annoyance, nor are his piano labors merely providing aural shade. No, Slim was a heavy-handed player in the best sense, and his piano embellishments and organ accompaniments are front-and-center, pushing forward Hutto’s emotional investments with great potency.

Both Lee Jackson and Herman Hassell provide excellent and required guitar support to Hutto’ slide guitar mastery, essential in their frameworks and in shaping of songs.

Junior Pettis and Dave Myers lend their bass support, and the growling undertones produced contribute further dark underpinnings to the tough brand of blues that Hutto urges forward. Their work roils with tension and advance the solemn messages of the tunes.

And Hutto, well, for a man of his diminutive stature, his vocals are an auditory bray. One wonders where the vocal power emanated from, but make no mistake, his vocals are forceful, forthright, and the perfect vehicle to convey his blues tales. His slide guitar work whines, screams, cries, and even subtly suggests the emotional backbone of one particular cut. Hutto’s overall work is razor-sharp and rough-hewn. It is the sound of the coarse life in Chicago’s black communities.

The one sideman on this collection who I believe was an odd choice for inclusion and adds nothing to Hutto’s work is Maurice McIntyre, a saxophone player in the Avant Garde mold. His bleats, squawks, and other cascading murmurs simply seem to detract from the otherwise excellent communal interplay here. Does it get enough in the way to ruin the whole of this collection? An emphatic “no” is the answer! But, again in my opinion, his exclusion from this work would’ve been to its benefit. As an aside, McIntyre did go on to record for Delmark under the names Maurice McIntyre and Kalaparusha Maurice McIntyre.

My greater hometown area includes South Bend, Indiana (five miles to my west), and the city has a rich blues history. Bluesmen who have called the city home include Sun recording artist Charly Booker, and Charly’s half-brother Tunney Watkins, a fine performer in his own right, lived in the city, as well. The great Albert King once called South Bend his home. Jr. Walker also was a resident of South Bend. Billy “Stix” Nix, a renowned Motown drummer, and the timekeeper for Jr. Walker and The All Stars, and a man who also drummed for Wilson Pickett, Sam & Dave, The Staple Singers, Marvin Gaye, and The Temptations, also lived in South Bend, and was a force on the city’s music scene until his passing. Pinetop Perkins lived in the greater South Bend area in his later years before his move to Austin, TX.

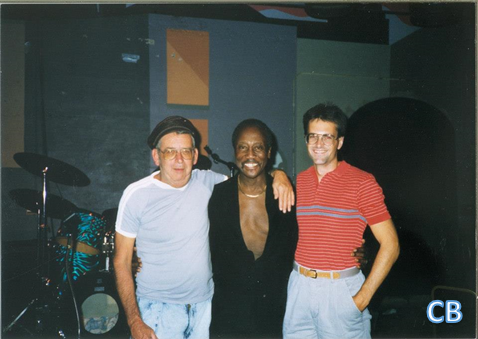

Over the years, South Bend had many venues to enjoy the blues, including the nearby University Of Notre Dame, where The Midwest Blues Festivals were held, Ribs & Blues on the city’s west side (Eddie Taylor guested there), and the original Vegetable Buddies, a downtown club that enjoyed a vigorous, albeit short run, from 1976-1980. Blues luminaries who played there included Willie Dixon, Muddy Waters, John Mayall, Dr. John, Luther Allison, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, Walter Horton, Taj Mahal, Koko Taylor, John Lee Hooker, Bogan and Armstrong, among others, including J.B. Hutto, as well.

There is a Wolf label release by J.B. Hutto and the New Hawks entitled Keeper Of The Flame. On the CD are seven tracks recorded “live” at Vegetable Buddies on July 11, 1979. The cuts find Hutto in fine form, with his vocals as exclamatory as ever, and his slide guitar work as cutting and exciting as ever. Hutto passed away four years later from cancer, but if he was suffering at all at the time of this South Bend recording, it certainly wasn’t apparent.

Mid-1960s Chicago blues was modern in the sense that by that time the electrified brand of post-war blues was fully realized, and the insistent moods of Chicago’s blacks were being brought to bear through a tougher brand of the music. The vocals commanded attention, the guitars screamed with emotive undercurrents, and the bluesmen who offered the music knew their audiences and the topics to address. J.B. Hutto, the bluesman of modest physical stature, adorned frequently with a fez, was yet another urban Chicago blues artist who knew how to express the personal outlooks of the city’s black population.

Hawk Squat comes highly recommended. A greater document of Chicago’s tough 1960s blues is tough to find. Modern blues did not originate with Hutto, but he helped create and nurture the modern Chicago blues sound. This is blues music at its best, and blues slide guitar of the highest order.